FULL TRANSCRIPT OF PODCAST LISTED BELOW BIO

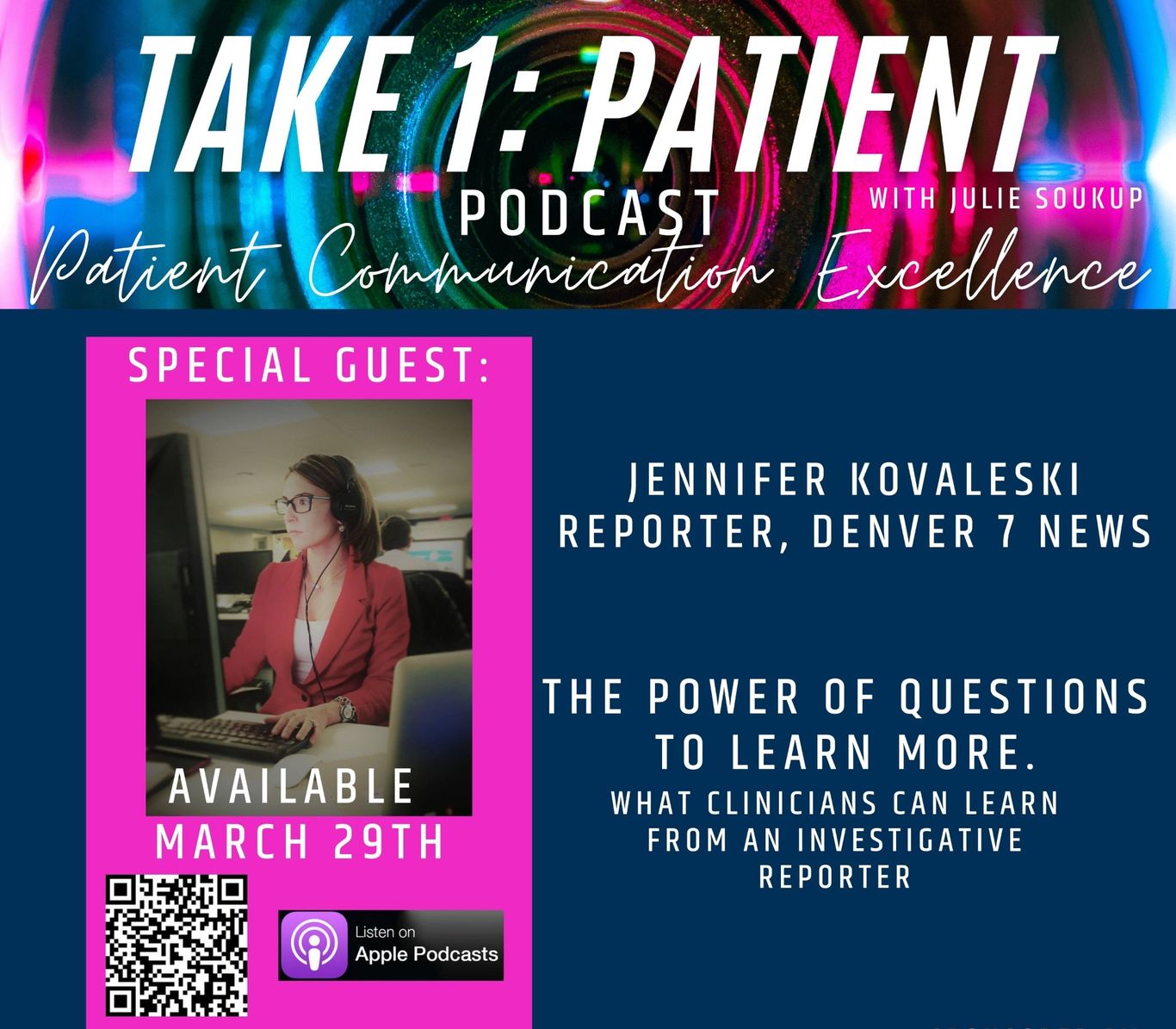

Jennifer Kovaleski, Investigative Reporter, 7 News Denver

Jennifer Kovaleski, Reporter for Denver 7 News joins our host Julie Soukup as we discuss how Providers and Nurses can use different question types and styles to be more efficient, and learn more about their patients. Jennifer shares with us the tips and tricks she has learned to help people feel comfortable, get to the story quickly (or patient story), and the few questions she asks in all interviews to get the most (and best) information.

Transcription of Podcast

Julie Soukup 0:01

with medical memory recording hundreds of 1000s of patients with their HIPAA compliant mobile app, we felt it was relevant to start discussing the best practices in patient communication, especially now that so many providers are recording these patient interactions with video. My name is Julia and I spent 15 years working with physicians to strengthen their communication skills. listen in as we learn tips from the industry's best in patient experience, how can we strengthen these patient and family conversations and help our nurses and providers optimize their time, especially now that the camera is on? So quiet on the set? Roll camera? This is scene one. Take one patient now. Action.

All right. Hi, it's Julie Sukup. with another episode of take one patient. I am very excited about this particular episode because we are actually talking to an expert and answering questions and asking questions, excuse me. So instead of looking just in our industry, and just looking at medical doctors and chief medical officers and nursing officers, we're looking a little bit outside of our scope. So Jennifer Kovaleski, is in investigative reporter with seven news in Denver. And she was originally introduced to medical memory when she did a story on our HIPAA compliant app. Right when COVID started, because we were one of the very few tools that were being utilized to record interactions with family members and with patients. And when they didn't have access into the hospital. And so that's where I was originally introduced to Jennifer. And I think one of the really things that she can provide a lot of insight and value to providers and nurses is in her ability to really ask questions and understand what's going on. So Jennifer, I'll let you kind of introduce yourself and your experience a little bit. Before we dive in. Thanks, Julie, I'm glad to be here, I was really struck by the work that you're doing at medical memory, we obviously did a story featuring your company and how you're bringing video into the hospital at a time when that was something that was really tough for families because they had loved ones who had COVID, who they were not able to visit they weren't able to talk to they didn't know what was going on. So seeing how you guys were bringing video into the hospital, I think really helped a lot of families. And really, during that difficult time, as we're still experiencing with COVID. But especially in the beginning, when there was so much more things were so much more uncertain. So it was it was really intriguing to learn about that. I think as you mentioned, I asked questions for a living. That's what I do. A lot of times people don't want us asking those questions as an investigative reporter. But I think through my work, you learn how to ask questions in a certain way to get to the truth. That's what we're really trying to do as journalists. And I think a doctor when they're going in is looking to get the truth of what's going on with their patient. And so it's similar in that way. Absolutely. And I think one of the interesting things and where we kind of started thinking about this, and the applications here is a recent study that we are looking at at doing in the emergency department in the emergency room. And one of the things that really struck me when we were looking at ways we could solve challenges in the ER and in discharge was when some of the leadership say hey, one of the biggest challenges or time gaps is patients that come in, they're upset, they're not really understanding what's happened to them, and not really understanding what what they need to do. Emotions are high pain is high, stress is high. And they find themselves repeating themselves, their story changing, you know, a lot of those different elements where a provider really has to dig in to really understand, you know, what, what has happened and what they can do about it. And so that's why I think this was really useful. And to kind of get your insight is, you know, how are you able to typically? Or what skills do you typically use to be able to really start asking, and kind of getting a,

you know, for you, it'd be I guess a source, but to a patient to understand what's happened or happening.

Jennifer Kovaleski 4:13

I think the biggest thing when you're asking questions is really focusing on that, why? Why are you here? What do I need to know, in terms of making sure that you're really getting at the why, and why is this happening? Why questions are always really something that we go to I also think listening is important. One of the biggest tips I would recommend when we've got a really tough interview or something where we've exposed something, and it may not be an interview that person wants but we're holding the powerful accountable is silence sometimes saying nothing at all, makes that person really take a step back and think about okay, well what's happening and they could just kind of start talking because nobody likes that awkward silence. So I've found that just pausing after you ask a question. Nobody likes to be uncomfortable. So they kind of start talking and that's something

When you get the best answers to your question, I also like to whenever I finished an interview, I always say, a little bit different for a doctor. But we always say things like, is there anything else that you wanted to add that I didn't mention? That's sometimes an opportunity, we get the best sound bites as we call them from that question, because something that maybe we didn't think to ask, they want to mention. And I think a doctor could use that in the same way of, hey, you know, we've talked about this, but was there anything else that you wanted to add or that you wanted to share that I didn't talk about? And maybe that's where some of that more of the truth comes out, or, Hey, I've been feeling this, and I didn't mention it. So those are some of the tips that I would use that I do use in interviews, to, to get to the truth and to make somebody comfortable. And I think that's a big part of it, too. A lot of times when I'm doing interviews, the person may never be comfortable, because we're we're there because they don't want us to be there, right? We're exposing something. But that's not always the case. A lot of times, we're talking to victims who have experienced tragedies, who have gone through a lot, they don't want to be in front of our cameras, but they're sharing a story about their loved one that they lost. So having that report and talking to them off camera, or in a doctor's perspective, having a conversation with them before they start asking those tough questions or those questions about their health, I think makes a really big difference.

Julie Soukup 6:20

Yeah. And it's interesting that you say that, you know, another one of our podcasts that we did with a gal who does cosmetic sales, was really talking about like framing, while you're asking it, like, I'm gonna ask you these questions because of XYZ or, or this is why these are these are gonna be asked a certain way, and just kind of explaining the why behind what you're asking and why you're asking it can oftentimes put someone at ease. So they're not feeling like, you know, the lights on you or something along those lines. And we're on the same team, you know, and trying to figure out what's going on and a call before we're wanting to

Jennifer Kovaleski 6:55

write, Let's expose the problem. Let's figure out what's going on with your health. I think those you know, are the same thing, just in different professions.

Julie Soukup 7:02

Yeah, absolutely. Well, and it's interesting, even though you say kind of your last question, which is, is there anything else that I didn't mention? You know, there has been a ton of research, you know, Carl Rogers, the founder of psychotherapy, a lot of our doctors we kind of have talked about before that leverage, okay, what are the tools, even of psychotherapy that are utilized to make somebody open up and empathetic listening and feeling comfortable to share, you know, the things that that are happening to them? And one of the biggest things that he was always said, is that that confirming of understanding at the very end where you're saying, Hey, this is what I got, is there anything else I missed? Is there anything else that you want to make mention of? And almost the most important thing to them? is almost what they'll say it right after that, because that's what's been weighing on their, on their heart or on their mind throughout that entire conversation.

Jennifer Kovaleski 7:49

Mm hmm. Well, exactly. To your point, I also think it's taking a step back and actually having the conversation I think, a lot of times when you're Go Go Go Your from one interview to the next or from one patient to the next, you're just kind of going through the motions. And sometimes I like to take a step back and say, Okay, we're here, let's let's talk to this person, let's get to know this person, not just ask the questions I know to ask, but really become a part of that conversation, really get to know that individual, which we all as life's busy, works busy, it's easy to kind of disconnect and go through the motions. But I think the most powerful interviews I've done are when you really become a part of that conversation, you get to know the person, and you're really engaged in what you're doing, and not just going through the motions,

Julie Soukup 8:34

right? Well, and as you said, sometimes maybe even that, that pause or that check in or kind of that breath before you're talking to that person, just tell them what's reset and say, okay, for for them this for me, this might be just my next interview, or for me, it might be this next patient. But for them, this is this is their story. And this is their struggle, and making sure almost like you reset, right before that. I think that's really awesome. Like as far as how you said that, too.

Jennifer Kovaleski 8:57

Yeah, no. And I think it makes a big difference. I think, just like anything, knowing somebody and getting to feel like they're on the same level as you in terms of that you want to solve this problem you're looking at what can we do for your health? Or how can we tell your story? How can we make a difference in the community. And that's really what we're looking to do. And so for us, it's interviewing as many people as we can to become, you know, experts on a topic. And I think from a doctor's perspective, it's maybe getting as many people involved in that person's health as possible, because maybe they won't tell you the full story, but their daughter knows a little bit more or their son knows a little bit more and and I know that doctors time is very valuable, and they only have so much but that's how we really peel back the layers and get to the bottom of the stories by getting to as many sources as we can. And I think that that's some of the same when you're talking about medicine and someone's health.

Julie Soukup 9:49

How do you typically and that's a great point, especially if someone's been brought in to the ER Because oftentimes, you know, there's other people that are there or when you do have an older patient or a child you know, That's the patient, how do you really kind of manage multiple people, when you are trying to understand something, especially when they're physically together to understand kind of what they're talking about what their story is.

Jennifer Kovaleski 10:12

So for when we've got multiple people on an interview, I think it's really the tactic that we use is to try to let the other person finish before the next person starts talking. Because I think a lot of times when you get a lot of people in a room, everybody's talking at the same time, you're trying to figure out what's going on. So I kind of always try to free minutes, I'm going to ask one question I want both of you to answer but let the other person finish before you start talking. Or I'll direct the question, if I think this person may be a little bit of a better expert in this area, I'll talk to that person first and then go to the other person. So I think it's really managing the room and managing who's there to kind of get what you need. Because I think in those situations, it can be difficult because especially when you're talking about someone's health, and especially if they're in the ER, and that means that things are bad. And you know, you're trying to figure out what's going on. And if your loved one, you're probably scared, and you're just talking, maybe you're rambling and kind of redirecting to say, Hey, what's going on, let's step take a step back, let's talk about, let's say on this topic, then we can go to the next topic. But letting that person feel heard, I think helps to alleviate some of that anxiety, maybe they're a little bit more comfortable talking about it. And they know that you're not just blowing them off. You want to hear about that. But right now, let's talk about this. And then we'll get back to that.

Julie Soukup 11:31

Right? Well, it's interesting even to when you're talking about just anxiety and some of those pieces is, is there's a ton of studies that have also been done about, you know, white coat syndrome, which is when you know, a doctor comes in, you almost freeze, and you don't want to say hey, yes, I haven't been watching, you know, what I'm eating, or I totally lied to my dentist last week, I was like, Oh, I love every day, like no, I go like, why am I lying to my doctor, like, you know, and, and so it's like that, like Coast syndrome of, you know, where, where patients will either just like kind of shut down, or just not be super, super straightforward. Obviously, like a doctor can kind of tell that, you know, when you are having situations where you can kind of see it something or or it's not really straightforward. A how do you how do you usually notice that and and be what are kind of the questions, you get to kind of refocus them or get them to like open up when you're like that's probably not entirely accurate, you know, in that capacity.

Jennifer Kovaleski 12:27

So I think the parallel with what we do is that a lot of times, we're exposing truth that maybe the person, the government agency, the company doesn't want exposed, we found something, someone's doing something wrong. And we're going to do a story and we want to ask you questions about it, we want to hold you accountable. That's our role as investigative journalists. I think that what I found when you're in those interviews is that a lot of times, it's hard for people to peel back that truth, you have to ask the question multiple times, you have to have the proof to say, hey, here it is, what do you have to say about this? And I find that you may have to ask that question multiple times to really get to the truth, or to get that person to acknowledge the truth. I think in the case of what you're talking about, with a patient not wanting to tell the truth, it's a little bit different, but it's somewhat similar. And that I think it's reframing the question not giving up until you get to the bottom of what's really going on. And sometimes that takes time. And sometimes that takes time. In our work. Sometimes we've got to get records, we've got to get multiple sources before an agency is going to say, Hey, we are going to fix something that we've had people come to us and say this isn't right, this company is doing us wrong, or you know, the local municipality isn't doing what they should be doing. So I think for a doctor's perspective, I feel like it's really not giving up and continuing to reframe that question until you get to what you think is the truth?

Julie Soukup 13:59

Sure. And when you're saying reframing, it's essentially the same question. Just asking it in a different way, or leveraging silence, like you said, is as powerful

Jennifer Kovaleski 14:09

as silence is a great way I think, because people don't like silence, it makes them uncomfortable. They don't know what to do. And so sometimes I think that's when you get a lot of that truth, because it is the truth, right? And sometimes it's harder to lie than it is to tell the truth. Right? So and when I talk about reframing, it is not letting the question go, right. So you keep asking it, and you don't let it go. And that's a lot of what we do in holding people accountable because them telling us a non answer. We don't accept that because we are asking questions on behalf of everyday people, and they want answers. And so we're going to keep asking that question until we get the answer because a lot of times in our work what we find, especially in the world where there's a lot of PR and public relations and people that are you know, give talking points to people before they do interviews With us, is you ask a question. And instead of answering the question, they just give you a talking point. And so you have to just keep asking it and keep asking it and pointing out that, hey, you're not answering my question. Because they're kind of taught to just keep telling you what they're supposed to say in the interview. And that's not normally the truth or the answer to the question

Julie Soukup 15:19

right. Now interesting. Well, and and kind of some of these situations, and one thing you made mention of is getting someone you know, to feel comfortable quickly, you know, oftentimes you have a bunch of things going on, you're doing things, you know, at multiple times, what what are kind of the tips that you use to kind of put someone at ease or build a little bit of trust quickly? Before you start, you know, digging into some of the questions that you may have. Here's the

Jennifer Kovaleski 15:47

reality. I mean, as a reporter, I've been with Denver seven, for almost eight years now, I started as a, what we call a general assignment reporter, and now I'm doing investigative work. And when I was a general assignment reporter, the sad reality is we cover bad news. We cover tragedies, we cover car crashes, we cover shootings, where people lose their loved ones. And so I've knocked on a lot of doors of people who have just lost their family members. And it's not an easy door, knock, I don't enjoy doing that. But it's just part of the job. And I think what I've always tried to do is to be human, and not just be a journalist. And so I've always kind of said something similar in terms of, Hey, I can't imagine what you're going through. Because I don't know, I've never lost a loved one in that way. But I'm here to let you have the opportunity to have your loved one remembered the way you want. And if you don't want to, that's up to you. But that's why I'm here, I'm not here to, you know, make this even harder for you, I understand you're grieving, this is just I want to give you the opportunity to have your loved one remembered the way that you want. And I think that that is somewhat similar in terms of its being human, it's so easy to kind of get into, you've got to do this, this and this, and not being human, and people don't gravitate towards that. And so you know, it's giving somebody a hug when they're having a really bad day. You know, I'm human to you. I live in this community, I am a part of this community. And so I don't think there's anything wrong with being human, especially when someone's going through something really tragic. And a lot of times when someone's at the doctor, they're going through something that they're trying to figure out, you know, you're it's a struggle, it's hard when you've got health issues, especially when you don't know what they are, you're trying to figure it out. Yeah,

Julie Soukup 17:35

well, and that's, it's interesting that you say that, because outside of me, we talked a little bit about the ER and how this is utilized. But for the most part, a lot of our physicians were utilizing medical memory before COVID Before, like in acute care where they were updating family members and providing these recordings to family members. We're using consultative space where a neurosurgeon or an ecologist, or an orthopedic surgeon is saying, hey, you need to have a major surgery, or you have cancer. And it's interesting, because one of our providers that we've been with for a really long time, in the oncology space, his biggest thing is, you know, I've got to pause to empathize before I say anything. And it was nice, because these patients and these family members had these video recordings. So they, you know, when they do go blank, they could review it, and they could share it with family members or anything along those lines. But even it was interesting, because some of the reviews of family members that were watched those videos, were like, We love this doctor, because because he his his whole motto was paused to empathize before I do anything, like take a minute just to empathize before we start getting into the medicine and we start getting into the, to the interview. So that's interesting that you said that, because it instantly made me made me think of the psychologist we've been working with for a really long time.

Jennifer Kovaleski 18:48

I think it makes a huge difference. I mean, just think about you if you were in their shoes, and I kind of tried to do that of how would I feel if some journalist is knocking on my door or to your point, if I'm going to get really terrible news about my loved one or about myself, having feeling like you have a connection with the person sharing that news, I imagine makes a huge difference in what is potentially the worst day of somebody's life.

Julie Soukup 19:11

Right? Absolutely. Now, one other thing that I think is interesting, and you work and has met a wide range of people, from from kids to elderly people, you know, many different cultures, races, all of those things. So one of the things that I think a lot of times providers sometimes struggle with is that we just actually did a podcast, the one right before this was speaking and talking and making sure people understand the level that that they can, and oftentimes, like Doctor lingo is so much more profound and bigger and bigger words that most your average person can understand. Probably a lot of similar similarities when you're dealing with government or legal issues. How do you kind of make sure that you're always like speaking you're asking questions to somebody on their own level are on like, Yeah, I mean, that's a really good,

Jennifer Kovaleski 20:04

I think, yeah, you're not getting too too big or too, you know, outside of, I try to keep them really simple and to keep them like really why questions. I mean, you're taught as a journalist always asked what they call open ended questions. So you're not asking yes or no questions. You're asking questions that, how did this happen? Why did this happen? And framing it in a way that allows for like, an open dialogue versus just did you do this? Yes. Um, yeah, exactly. And I think that's, you know, how are you feeling? Versus Did you feel that? Did you feel that and I think that's a lot of the medical field, you fill out all those forms? It's, do you have this symptom? Do you have that symptom, but having that open dialogue, I think it changes, it changes the conversation with your doctor. I mean, when you're having a real what you feel is like a real conversation that isn't just checking boxes, I think you're probably more honest with your doctor, you feel better about that interaction, you go home feeling like your doctor cares. And I think it's similar in what we do in that people are trusting us with their stories. And I don't take that lightly. When people come to us, they're sharing their story with us that we're then sharing with the world to hopefully make a difference. And that takes a lot of guts because they don't write the story. They're trusting us to tell their story the way that they presented it to us. So it's also our job to really figure out what the story is, and make sure we understand what they're hoping to get across and what they've been through. And I think that it's similar for a doctor, they're there to sometimes give bad news, but also help understand what's going on with that patient, often in a short amount of time. And we're on deadline a lot. That's the reality of working in local TV news, especially as a general assignment reporter, you start your day at 930. In the morning, in the morning, call in when you have a general sense, reporter, you have to turn a story for that day. So that means you have to get all of your interviews, and write a story for the five or six o'clock news. That's not a whole lot of time. And so you've got to get to the bottom of whatever is going on, you have to be able to be an expert on something in a very short amount of time. And doctors are obviously experts in their field. But I think it's similar in that they have limited time. And they're trying to figure out what's going on with a lot of different patients dealing with a lot of different things.

Julie Soukup 22:29

Yeah, absolutely. And I think that kind of the, you know, to sum up some of the main points or doesn't say like the three things that that I think you're really saying, who could be utilizing this space is that first kind of like, pause before you're talking to someone, you know, take that moment to be to be human in the beginning. I think definitely hearing you know, just being quiet that still that, you know, letting people kind of give you the information sometimes without asking a bunch of questions, like the best question is not a question.

Jennifer Kovaleski 22:58

Yeah, absolutely. I think silence is key.

Julie Soukup 23:01

What else are you What else, you know, anything I missed, or anything else you want to kind of talk about? And I think those are all like three incredibly relevant places, kind of that tie in almost immediately to the medical field.

Jennifer Kovaleski 23:14

Absolutely. And I think that in a lot of what we do in our recording, we do a lot of what we call 360 reporting, which is kind of like in depth, we want to get all the different perspectives on a story. And I think that's similar to what doctors are doing too. And what we're all trying to do, especially in this in today's world where there is so much information out there. It's getting all of the information and all of the sources and making those people feel comfortable. I think you really summarize kind of what what I tried to do. And what is really important as being a journalist is, is also being human. And I think it's important for doctors to be human too.

Julie Soukup 23:48

Awesome. No, absolutely. Is there anything else you'd like to add or anything I missed? See?

Jennifer Kovaleski 23:55

I'll give the best part of the whole podcast right here.

Julie Soukup 23:58

Yeah, right. Well, awesome. Well, thank you so much for your intellect, your wisdom, we I so appreciate, you know, what you do as a profession. And I think there's a lot that we can kind of learn, you know, kind of looking a little outside of our own space, especially when it comes to really, you know, leveraging open ended questions, leveraging silence, you know, leveraging that anything, I miss kind of pieces to make sure that our providers are, you know, using the time they have as effectively as possible to really understand it gets other patients better in that in that capacity. So, thank you so much for your time, and we'll hopefully talk to you again soon.

Jennifer Kovaleski 24:35

Yes, yes. Thank you for having me.

Julie Soukup 24:37

All right. And cut. Thank you for joining us on this episode of take one patient. We hope you have a nugget or two you can implement into your practice with your patients today. For more information about recording your visits with a HIPAA compliant app, go to www.va Medical memory.com or you can follow me on Instagram at duly recording doctors thanks again

Transcribed by https://otter.ai

© Copyright. All rights reserved.

We need your consent to load the translations

We use a third-party service to translate the website content that may collect data about your activity. Please review the details in the privacy policy and accept the service to view the translations.